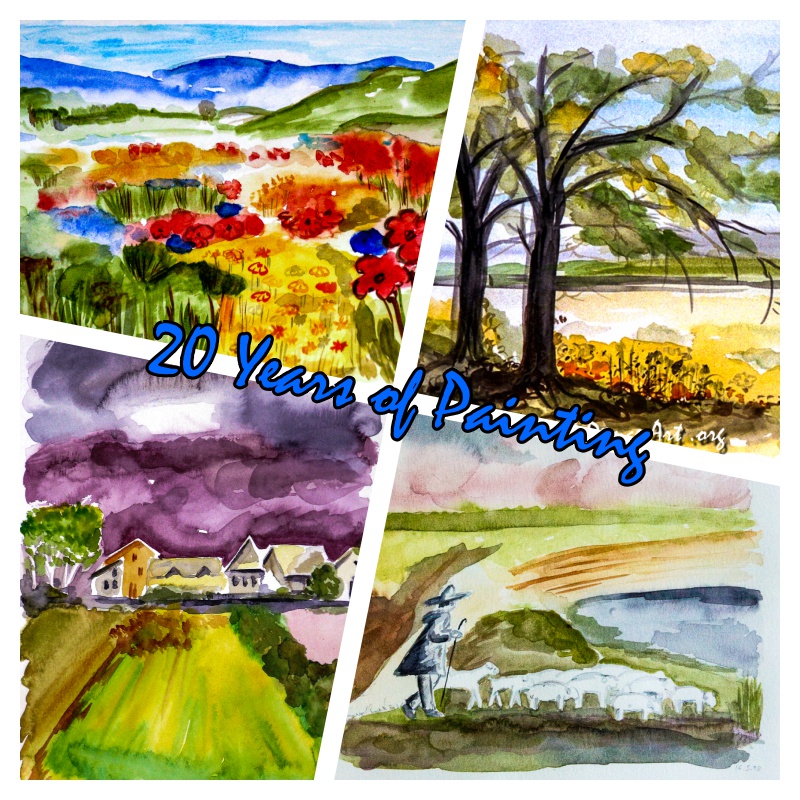

Anniversary – 20 Years of Painting.

Today, I am celebrating 20 years of painting. 20 years ago I attended my first watercolor painting workshop at an adult education center in the Siegerland (Germany). At that time I painted my first four pictures – in ONE day! And the rest is history, as they say.

The four watercolors shown above were my first four paintings that I painted 20 years ago today. Hard to believe it’s been that long. I had no idea then what would come of it.

Good things come to those who wait

I had been planning this for a long time. Several years before I had heard for the first time that there is such a thing as painting courses for adults. I really wanted to do that! But because of my job abroad and all the traveling, it was not possible for a long time.

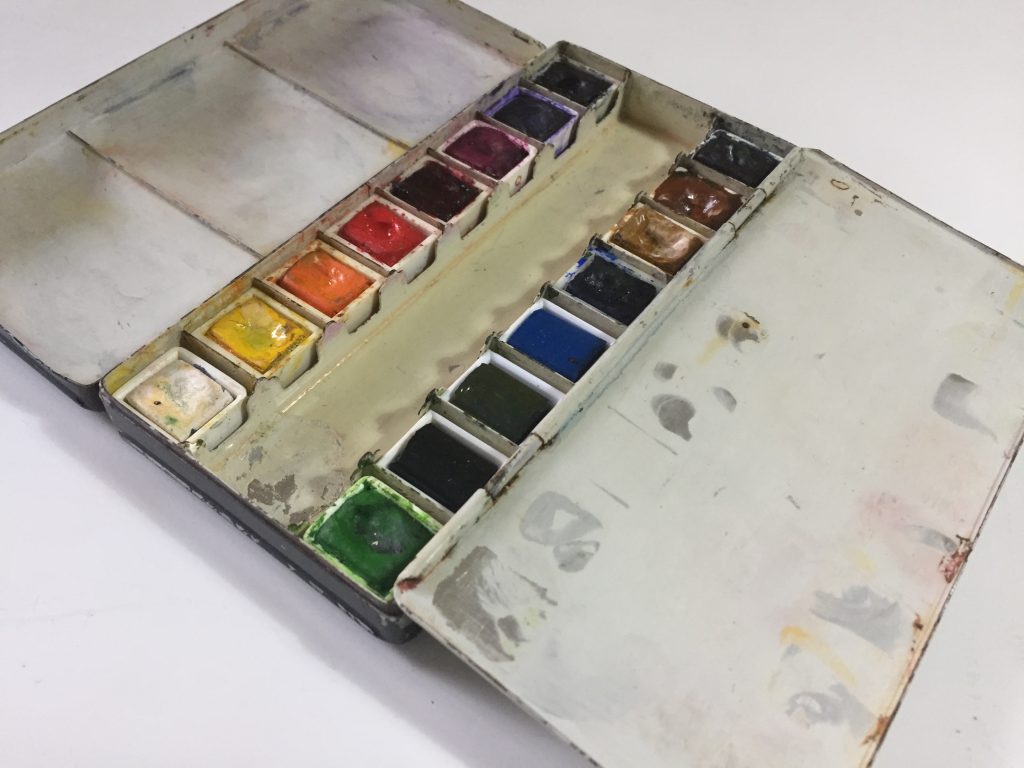

All the time I had this small watercolor paint box that I had inherited from my grandfather. A real museum piece. In 1998 it was finally put to good use. The paints contained in it had long since dried out or stuck to the lid. No wonder, since my grandfather had died in 1980. But I found matching cups in the art shop. Unfortunately, I cleaned the paint box too thoroughly at that time and some of the paint came off. 🙁

With this paint box and some other utensils, I set off. And this although I was still on sick leave. But I didn’t want to miss the workshop. I’ve waited too long for this kind of opportunity! Although I was still physically weak, I made it through the weekend ok. The result of these two days was eight watercolors that surprised me. Of course, this motivated me to continue painting afterward.

Watercolor as my preferred medium

For a long time, watercolor was my favorite medium. I noticed that especially when I painted again after a long break. I always picked up the watercolors first. For purely practical reasons, watercolors were also my first choice when I was traveling.

Meanwhile, there are of course many other painting media that I use often. More about that another time.

What are your favorite media – either for painting if you are an artist yourself, or for viewing art if you are an art lover? Does it have to do with which painting media you got started?

Write your thoughts on this in the comments.